The Best of 2008

Still, even if the other posts on this blog can't quite live up to that standard, I still think they're somewhat interesting, and worth a visit.

From January:

Shout-outs to my mentors in urban wilderness appreciation: Mark Dion and William Cronon. I was also on a bit of a militaristic kick a year ago, with posts on Korea's DMZ wilderness area and the military heritage of European-style boulevards.

From February:

The next manifest destiny for the American west: parched and scorched suburbs. Speaking of suburbs, land trusts in wealthy suburban communities like Cape Elizabeth, a blue-blooded coastal suburb of Portland, are more interested in preserving real estate values than they are in providing real environmental benefits.

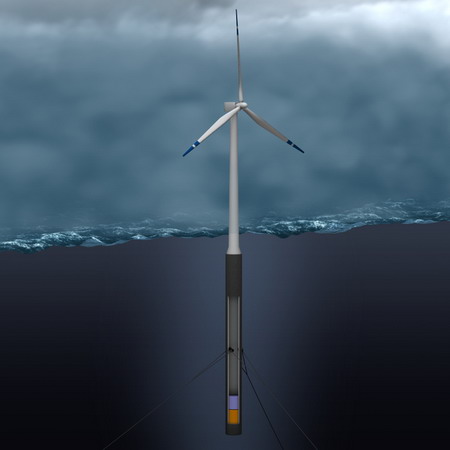

A new wind turbine rivals the downtown garbage incinerator's smokestack in a small Maine city's skyline.

From March:

More on the Manifest Destiny and "American Progress," the way it looked 130 years ago.

Action and adventure: I scale Portland's Bayside Glacier! A few days later I witness a bloody mid-air battle a few blocks from my house (and get some gruesome photos to prove it!).

And during spring break in Houston, we visit the Ocean Star Offshore Energy Museum: marvel at the Gulf Coast's incredible money machines.

From April:

With energy and food prices rising in tandem, ethanol would appeal to Marie Antoinette, I think: Energy crisis? Let them burn cake.

I also dig through Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's old basement and find some victorian-era junk before they bury it all under a new hotel in downtown Portland.

From May:

The growth of city street networks follows the same mathematical pattern as the growth of leaf capillaries or cells in living organs: cities are organic. May is plastic blogging month at the Vigorous North: I write about Portland's plastic spring foliage, and the Pacific Ocean's floating plastic island. Recycling plastic is a no-no in Berkeley, but it might be OK in Maine.

From June:

A proposal for new storm drain stencils. The geography of "cyberspace" is fading away, but the human ideome project is just beginning.

The foreclosure crisis transforms swimming pools into vernal pools throughout the Sun Belt.

Maine's working waterfronts used to rely on local natural resources, like our fisheries and timber. Now, military contracts keep our few remaining shipyards in business.

From July:

America means choice: comeuppance for Ford and General Motors.

New parks are exhuming pieces of London's ancient rivers.

From August:

Monuments in city parks? Nature abhors a statue. It's summer in Maine, blogging takes a break.

From September:

Ike bears down on Texas, and I write about how Galveston lifted itself up (literally) after the devastating 1900 hurricane.

Portlandhenge, LAhenge, DChenge, and the autumnal equinox.

Sometimes, inner-city "open space" is bad for the environment.

From October:

A hiking guide to Portland's Stroudwater Trail.

An urban wildlife guide to the Virginia Opossum, the spirit animal of President Taft.

Hundreds pack a Lewiston chapel to hear

From November:

Wildlife corridors in Pittsburgh, and other inner-city wilderness areas in the news.

The big story, thanks to attention from Kottke.org and many others, was about how Obama owed his success in the deep south to the rich, loamy soils laid down 85 million years ago, in the late Cretaceous period. Down in Dixie, the blue counties have black people and black soil; red counties have red clay.

From December:

A $17 billion tour of the fabulous ruins of Detroit.

Urban snapping turtles as "the fatty palimpsest on which the toxic legacies of our lakes and rivers are chronicled."

Portlandhenge returns: the winter solstice on Winter Street.

Happy new year!

A concept drawing of a floating wind turbine, using technology from floating oil-drilling rigs. From

A concept drawing of a floating wind turbine, using technology from floating oil-drilling rigs. From