Hedging for the End of Civilization, Part II

While we're talking about the collapse of the global economy, and civilization in general, I should also mention that there are a lot of people who do expect something along these lines to actually happen. Perhaps not surprisingly, many of them can be found talking about it on the internet.

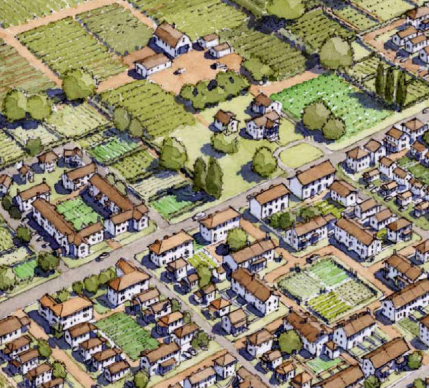

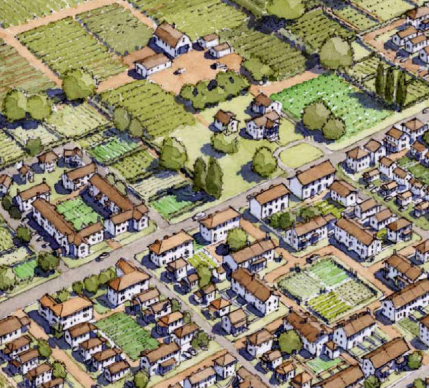

Architect Andres Duany thinks that peak oil and escalating food prices should convince real estate investors to build hobby farm collectives instead of golfing communities. For a million-dollar investment, your post-collapse future can look just like Tuscany! From "New Urbanism for the Apocalypse," by Greg Lindsay for Fast Company.

For instance, there's Wendy, the Surviving the Apocalypse in the Suburbs blogger, who lives and writes from somewhere near me in southern Maine, and is trying to transition her family to a more "self-sufficient" lifestyle.

Architect Andres Duany thinks that peak oil and escalating food prices should convince real estate investors to build hobby farm collectives instead of golfing communities. For a million-dollar investment, your post-collapse future can look just like Tuscany! From "New Urbanism for the Apocalypse," by Greg Lindsay for Fast Company.

And I'm especially fond of the Urban Self-Sufficientist in Atlanta. He raises rabbits and grows veggies in the backyard of his in-town bungalow, but the best posts are about practicing falconry in local parks in order to enjoy homemade, free-range squirrel stew.

It's interesting how these different people pursue "self-sufficiency" in different ways. Wendy, for instance, makes much of growing her own food, but she still lives in a suburb where she's forced to pay for two cars and their fuel in order to acquire basic necessities. How's she going to find enough refined oil to fill her cars' tanks after civilization collapses?

Meanwhile, the Urban Self-Sufficientist takes an opposite tack, living in the middle of an urban neighborhood. If gasoline disappears, he won't be too put out - but won't his neighbors start taking an unsavory interest in the fruits of his backyard farm?

And architect Duany talks up economic collapse even while he tries to get real estate investors to build his planned communities, which will presumably be financed by 30-year mortgages. At least he's talking with people who ought to be experts in economic failure.

So even people who are planning for disaster clearly have different expectations of what it's going to be like: different people hedge for the end of civilization in different ways. Some believe that through the wreckage we'll figure out some way to keep our cars; others believe that we'll figure out a way to maintain a financial system.

I have my doubts on these counts - you're going to put more faith in American car culture than in America itself? - but then again, I also don't think it's much worthwhile to plan for any kind of collapse. Even if it does happen, it's going to be unpredictable.

Besides, I'm not much interested in self-sufficiency for its own sake. I'd rather rely on my neighbors for some things - there are plenty of people who are better farmers than I am, for instance, and I'd rather let others do the things they do well rather than try to do everything half-assed by myself. Specialization of labor is one of the innovations that got humanity out of the stone age, and even if civilization did collapse, I would hope that we wouldn't need to leave that idea behind - that we'd still be able to rely on our neighbors, families, and friends to help each other out.

Still, I do enjoy how the idea of self-sufficiency leads people to think about the places and the resources that provide their necessities for living. It's a roundabout way of thinking about our day-to-day relationships and dependencies on the natural resources that sustain us, and for some (like the falconer in Atlanta) it's a way to bring a little wildness home with us, even if we live in the middle of the city.

Self-sufficiency will not be any fun if it's forced on us. But as long as it's an elective activity, these bloggers make it clear that it can be a rewarding pursuit.