Creative Destruction

"The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them. And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones. That is to say, by paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises...""New York, you're perfect

Don't please don't change a thing

Your mild billionaire mayor's

Now convinced he's a king

So the boring collect

I mean all disrespect

In the neighborhood bars

I'd once dreamt I would drink."

- LCD Soundsystem, "New York, I Love You But You're Bringing Me Down"

We live in a nation that no longer makes things, and maybe that's why we're so foggy-headed when it comes to discussions of wealth, class, or even of basic entrepreneurial instinct. How can we hope to understand wealth when "luxury" is pitched to us as a shoddily-built McMansion, and twenty years' worth of retirement savings can disappear in a stock market crash? What does it mean to speak of labor when work is a mind-numbing interval in a cubicle?

Maybe this economic existentialism is also why it's so popular to talk about the "creative economy" these days. Creative industries hold the last vestiges of America's tangible economic output - our last chance to make anything for ourselves.

On the surface, this seems like a positive thing - who wouldn't want more creativity? After chasing smokestacks for decades, City Hall is bringing a long-overdue focus on the small businesses and vibrant neighborhoods that really make our cities welcoming and attractive.

And yet (if the fad comment hasn't already tipped you off) it's beginning to feel like a lot of bullshit to me.

The Marfa Prada, a half-joking commentary on "Judd-effect gentrification", on the plains outside of Marfa, Texas. Photo via eartharchitecture.org.

And yet (if the fad comment hasn't already tipped you off) it's beginning to feel like a lot of bullshit to me.

The germ of my ambivalence came from a real estate development proposal in my neighborhood. A billionaire hedge fund manager (and the husband of our congresswoman) owns a pied-à-terre apartment a few blocks away from us, and wants to transform several of the area's working-class tenement buildings that are in his portfolio into a newly renovated cluster of live-work spaces for quote-necessitated-because-I-don't-really-trust-a-billionaire-hedge-fund-manager's-use-of-the-word-unquote "artists".

So. I have some issues with said hedge fund manager's imposition of his aesthetic values on the landscape of our neighborhood, and on the creative output of local artists vis-a-vis the terms of their rental agreements. That's one thing and it might be entirely unjustified.

But I feel more nervous - and more certainly justified in this unease - about how the hedge funded artist colony is going to affect the larger creative environment of the city at large.

His proposed development is located on one of the last working-class neighborhoods of the city. It was part of Portland's Little Italy, and it's one of the few immigrant neighborhoods that wasn't demolished during the urban renewal purges of the 1960s and 1970s.

So. I have some issues with said hedge fund manager's imposition of his aesthetic values on the landscape of our neighborhood, and on the creative output of local artists vis-a-vis the terms of their rental agreements. That's one thing and it might be entirely unjustified.

But I feel more nervous - and more certainly justified in this unease - about how the hedge funded artist colony is going to affect the larger creative environment of the city at large.

His proposed development is located on one of the last working-class neighborhoods of the city. It was part of Portland's Little Italy, and it's one of the few immigrant neighborhoods that wasn't demolished during the urban renewal purges of the 1960s and 1970s.

At one end of the street is the city's friendliest dive bar; at the other end is a day labor agency. It happens to be a pretty great place for artists to live and work right now, as it is. But it's also a great place where teachers, hotel workers, office cleaners, and dozens of other working-class families can still afford to live, within walking distance of downtown's jobs and services. Why would we want to kick those people out?

Simultaneously (and potentially relatedly), a number of the city's economic development professionals and business leaders have recruited ArtSpace, a nonprofit developer of affordable buildings for artists, to investigate the possibility of their developing a project in Portland (possibly on Hampshire Street, and possibly elsewhere).

It may seem counter-intuitive, but even if we did create a walled garden for artists here - and it matters little whether it's built by a hedge fund manager or a nonprofit institution - the experiences of numerous other cities and neighborhoods before us forebodes that the wealth it brings in pursuit of "creative" entertainments will jeopardize the neighborhood's affordability and diversity, and thus undermine the fertile conditions that generate the very creativity we value.

Look at New York City: wealth drove out artists first from SoHo into the Lower East Side, then into Williamsburg, and now deep into Bed-Stuy. If the southeastward exile continues, in thirty more years all the artists will be drowned in the waters of Jamaica Bay.

Forty years ago, Donald Judd tried to escape it by moving from Manhattan to live among ranchers in a miniscule town in west Texas. Today, even that miniscule town is itself losing its identity with the influx of more and more wealth.

The Marfa Prada, a half-joking commentary on "Judd-effect gentrification", on the plains outside of Marfa, Texas. Photo via eartharchitecture.org.

And I saw it happen firsthand in Portland, Oregon, at the turn of this century:

But we live in a city, and cities are meant to change. Creative destruction, after all, is still creative. If one neighborhood becomes boring, another will become interesting. House shows will spring up in unexpected places; empty warehouses or abandoned big-box stores will become artists' squats. If we, as a city, embrace change (and Portland, to own the truth, has some issues with this, a few hang-ups with its nostalgia for the status-quo), then creativity has a way of surviving.

In 1999, I set off to go to college in Portland, Oregon — then known only as a rainy mid-sized city with scenic parks. In the five years I spent out there, I saw the city morph into a self-satisfied model of progressive hedonism. But, as I found after graduation in 2003, and as thousands of other young people have found since then, it’s awfully hard to land a decent job there, and it’s getting harder all the time to find an affordable place to live. (source)

A creative economy requires creative people, and creative people seek out the frisson of affordable, diverse city neighborhoods, where it's easy to discover and interact with new ideas and with people who possess a diversity of cultural and economic backgrounds.

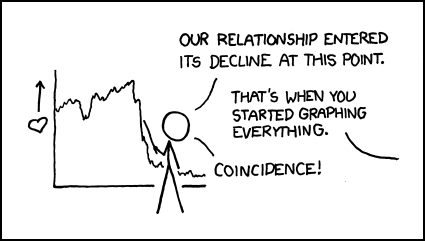

Creative people also require capital: they need affordable places where they can live and create things. But creativity, after all, is fun to be around: it attracts wealth, which ends up competing for the same resources that the creative people need. Thus, to paraphrase Marx, the accumulation of creative capital sows the seeds of its own destruction.

Sure, you can create protected islands of creativity amidst the sterile ruins of luxury condos and fusion restaurants. That's what the hedge fund manager and Artspace want to do, and I suppose that in some circumstances that might be the best option. But how creative can such a place really be, in its isolation? And aren't we declaring defeat prematurely by pursuing that option so soon, while our neighborhoods are still fairly egalitarian and diverse and functional just the way they are?

More importantly, is the exile of creative people from the neighborhoods they make great inevitable? Is the "creative economy" just the post-industrial manifestation of Marx's inevitable creative destruction?

Admittedly, the track record from places like New York isn't great. But I think there are two reasons to be optimistic.

I often think of Houston, where I lived for a year, as one of the most creative places I've lived (it certainly had Portland, Oregon beat). Sure, miles and miles of the city were dead zones of strip malls and cul de sacs. But for every time someone bulldozed a historic edifice to build a Wal Mart, someone else was doing something amazing in a vacant rice factory or shotgun house they bought for dirt cheap. That city thrived on constant change. From the outside, the city might look monstrous, constantly consuming itself and spreading out larger and larger. But on the ground, there was always something new.

If we lose Hampshire Street to a bunch of navel-gazing painters who are condemned to mediocrity because they never meet anyone or anything that challenges their assumptions, then I'll be sad, not least because that's my very own neighborhood that will become a more boring place.

But we live in a city, and cities are meant to change. Creative destruction, after all, is still creative. If one neighborhood becomes boring, another will become interesting. House shows will spring up in unexpected places; empty warehouses or abandoned big-box stores will become artists' squats. If we, as a city, embrace change (and Portland, to own the truth, has some issues with this, a few hang-ups with its nostalgia for the status-quo), then creativity has a way of surviving.

Still, I'd still rather let it thrive. And that brings me to a second reason to have some hope, because here we have a billionaire who wants to do right by downtrodden artists, and it seems churlish to complain about his methods when the impulse carries so much possibility.

If I ever had the chance to meet my billionaire neighbor, this is what I would tell him.

Portland's neighborhoods aren't ruined yet - they're still by and large egalitarian, and affordable, and authentically creative. Even better, a lot of the wealth that might threaten those neighborhoods' creativity is possessed by people who actively want to support a creative environment.

You and the other creative economy boosters want to do the right thing by carving out a refuge for artists - but you haven't yet considered the consequences of how that kind of project could exile dozens of other people who may not make art per se but are nevertheless vital to maintaining the conditions of a creative city.

May I suggest instead diverting your considerable resources toward finding ideas and investments that make the city more equitable and affordable to all people, not just for "artists"? If we can accomplish that, then the entire city stands a better chance of fostering the ideal conditions that generate more and more creative places.

Instead of relying on an institution to build us one Artspace, we could build hundred of Artspaces for ourselves, on our own terms, to our own standards. Sounds good - am I right?

If I ever had the chance to meet my billionaire neighbor, this is what I would tell him.

Portland's neighborhoods aren't ruined yet - they're still by and large egalitarian, and affordable, and authentically creative. Even better, a lot of the wealth that might threaten those neighborhoods' creativity is possessed by people who actively want to support a creative environment.

You and the other creative economy boosters want to do the right thing by carving out a refuge for artists - but you haven't yet considered the consequences of how that kind of project could exile dozens of other people who may not make art per se but are nevertheless vital to maintaining the conditions of a creative city.

May I suggest instead diverting your considerable resources toward finding ideas and investments that make the city more equitable and affordable to all people, not just for "artists"? If we can accomplish that, then the entire city stands a better chance of fostering the ideal conditions that generate more and more creative places.

Instead of relying on an institution to build us one Artspace, we could build hundred of Artspaces for ourselves, on our own terms, to our own standards. Sounds good - am I right?

Postscript: I've started writing a biweekly column in a small local paper, the Portland Daily Sun, and I wrote on this subject last week. But 800 words wasn't enough to fit in all the nuances of my mixed feelings about the "creative economy" business, hence this elaboration.