Creative Destruction

"The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them. And how does the bourgeoisie get over these crises? On the one hand by enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces; on the other, by the conquest of new markets, and by the more thorough exploitation of the old ones. That is to say, by paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises...""New York, you're perfect

Don't please don't change a thing

Your mild billionaire mayor's

Now convinced he's a king

So the boring collect

I mean all disrespect

In the neighborhood bars

I'd once dreamt I would drink."

- LCD Soundsystem, "New York, I Love You But You're Bringing Me Down"

And yet (if the fad comment hasn't already tipped you off) it's beginning to feel like a lot of bullshit to me.

So. I have some issues with said hedge fund manager's imposition of his aesthetic values on the landscape of our neighborhood, and on the creative output of local artists vis-a-vis the terms of their rental agreements. That's one thing and it might be entirely unjustified.

But I feel more nervous - and more certainly justified in this unease - about how the hedge funded artist colony is going to affect the larger creative environment of the city at large.

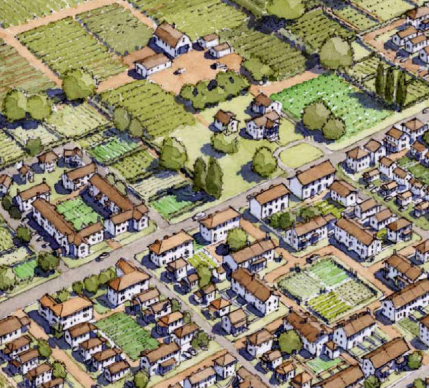

His proposed development is located on one of the last working-class neighborhoods of the city. It was part of Portland's Little Italy, and it's one of the few immigrant neighborhoods that wasn't demolished during the urban renewal purges of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Marfa Prada, a half-joking commentary on "Judd-effect gentrification", on the plains outside of Marfa, Texas. Photo via eartharchitecture.org.

In 1999, I set off to go to college in Portland, Oregon — then known only as a rainy mid-sized city with scenic parks. In the five years I spent out there, I saw the city morph into a self-satisfied model of progressive hedonism. But, as I found after graduation in 2003, and as thousands of other young people have found since then, it’s awfully hard to land a decent job there, and it’s getting harder all the time to find an affordable place to live. (source)

But we live in a city, and cities are meant to change. Creative destruction, after all, is still creative. If one neighborhood becomes boring, another will become interesting. House shows will spring up in unexpected places; empty warehouses or abandoned big-box stores will become artists' squats. If we, as a city, embrace change (and Portland, to own the truth, has some issues with this, a few hang-ups with its nostalgia for the status-quo), then creativity has a way of surviving.

If I ever had the chance to meet my billionaire neighbor, this is what I would tell him.

Portland's neighborhoods aren't ruined yet - they're still by and large egalitarian, and affordable, and authentically creative. Even better, a lot of the wealth that might threaten those neighborhoods' creativity is possessed by people who actively want to support a creative environment.

You and the other creative economy boosters want to do the right thing by carving out a refuge for artists - but you haven't yet considered the consequences of how that kind of project could exile dozens of other people who may not make art per se but are nevertheless vital to maintaining the conditions of a creative city.

May I suggest instead diverting your considerable resources toward finding ideas and investments that make the city more equitable and affordable to all people, not just for "artists"? If we can accomplish that, then the entire city stands a better chance of fostering the ideal conditions that generate more and more creative places.

Instead of relying on an institution to build us one Artspace, we could build hundred of Artspaces for ourselves, on our own terms, to our own standards. Sounds good - am I right?

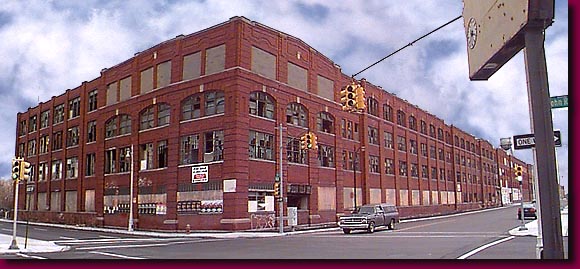

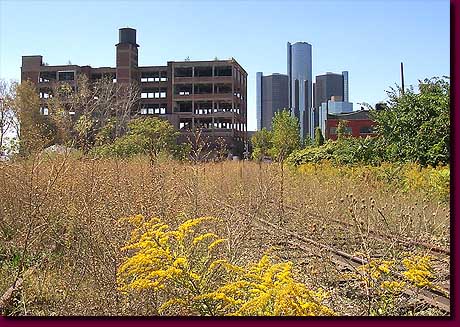

Photo: Jason Levine

Photo: Jason Levine

The High Line, scraped clean and ready for new landscaping, while secondary-growth condos and Gehry emerge from the weeds in Chelsea. Photo: NYVviaRachel on Flickr

The High Line, scraped clean and ready for new landscaping, while secondary-growth condos and Gehry emerge from the weeds in Chelsea. Photo: NYVviaRachel on Flickr