How an Icon of Journalism Became a Hollowed-Out Billboard

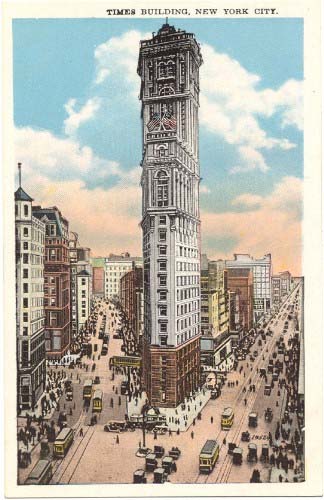

When it was built at the southern end of Longacre Square in 1903, the new headquarters of the New York Times became a landmark of midtown Manhattan, and helped publisher Adolph Ochs convince the city to rename the famous intersection in front of the building as Times Square.

By the mid-20th century, though, the Times had sold the building, and a new owner dismantled the intricate granite and terra-cotta facade to replace the exterior walls with plain concrete panels. In 1996, shortly after the City Council passed new laws that expelled porn theaters from the area, the building got sold again, to Sherwood Outdoor, an advertising firm. By then, the building's signage was covering most of the exterior windows, leaving the offices inside rather dark and dreary.

Rather than spend money to renovate, the new owners decided to simply abandon the building's interior above the 3rd floor, and use the top part of the building exclusively as a billboard (the lower 3 floors are still used, periodically, as retail space — it's currently a Walgreens drug store).

So for the past 15 years, the iconic building that was the namesake of Times Square itself, and a major headquarters of journalism, has become a hollowed-out shell, a mere scaffold for electronic signs.

At the Crossroads of the World, the value of advertising has trumped the value of journalism, and of work in general.

Postscript: Illustrator Joe Mckendry has made a gorgeous before-and-after elevation drawing of the building's eastern facade in 1904 and in 2010, for his book One Times Square.

|

|

| One Times Square in 1904 (source). | One Times Square in 2010. Photo: Bernt Rostad/Flickr |

So for the past 15 years, the iconic building that was the namesake of Times Square itself, and a major headquarters of journalism, has become a hollowed-out shell, a mere scaffold for electronic signs.

At the Crossroads of the World, the value of advertising has trumped the value of journalism, and of work in general.

Postscript: Illustrator Joe Mckendry has made a gorgeous before-and-after elevation drawing of the building's eastern facade in 1904 and in 2010, for his book One Times Square.