I've been spending this week in Tampa, Florida for a new website that my employer is building. Before I'd left I'd asked lots of people for travel advice, but even people who'd been here before didn't have much to recommend. So, on my first day here, when we got out of work early for the day, I took a long walk with no particular destination in mind: what the psychogeographers would call a

dérive.

We're staying in a pastel-colored high-rise hotel near the convention center and hockey arena, a neighborhood where all the buildings have apparently been built in the past 20 years.

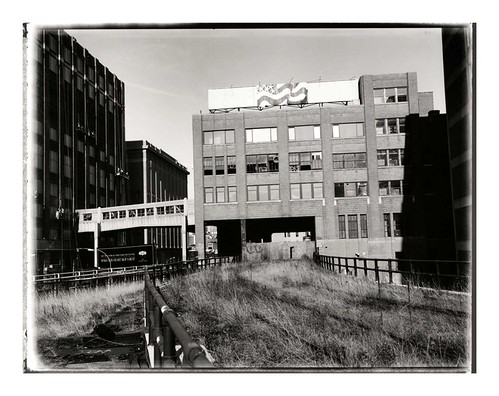

The district's newness led me to presume that it had been, until recently,

some kind of waterfront industrial area, or railroad depot, demolished during the

urban renewal fads of the 1960s and 1970s and only just now rebuilding.

But as I walked north into the heart of downtown Tampa, I only found similar neighborhoods and buildings.

It seems as though almost all of Tampa had been torn down in the last 30 to 40 years, and replaced with a landscape like this:

As I continued northward into the center of the downtown, the street I was on became barricaded to car traffic, and a lush tropical

garden replaced the asphalt. It was here, after four blocks of walking near the end of the workday on a pleasant

Tuesday afternoon, that I encountered my first fellow pedestrian.

The street I was on appeared to be the city's attempt to recreate the kinds of "festival marketplaces"

that had been faddish in the 1980s, like Baltimore's Inner Harbor or Boston's Quincy Market.

A dated building with steel

bay windows faced the pedestrianized street with abandoned kiosks, empty arcades, and faded signs that referred to its address as "city center," as though recalling its glory days.

And then there was this "Municipal Building".

On the other side, nestled in the rear corner of the concrete fortress, I found one of the few old buildings in the city.

I detoured half a block to find that this was the old City Hall, still occupied by some of the city's more fortunate bureaucrats.

Changing course to the west, I cut diagonally through a tree-lined downtown square to Tampa Street,

where there was a small cluster of non-chain businesses somehow subsisting on the downtown's tiny trickle of foot traffic.

There, I found a used bookstore with an impressive collection of old and rare volumes.

I learned, from a circa 1979 Chamber of Commerce coffee table book, that Tampa had been a center of cigar manufacture

and a major railroad depot in the nineteenth century. There book also had several photos of an impressive

turn-of-the century grand hotel, just across the Hillsborough River from downtown,

which was still standing and had been incorporated into the University of Tampa campus.

I struck out west toward the river to see the building for myself and rested a while by the river while a rowing team went by.

Turning around, back towards downtown, I was confronted with a less impressive view of two condo high-rises, buttressed with huge parking garages.

The downtown skyline is twice as high as it otherwise would be, thanks to these garages, which squat underneath

virtually every high-rise.

Tampans must spend hours driving on their indoor ramps, spiraling up to store their cars on the 7th and 8th

stories of their office buildings in the morning, then spiraling down again to drive home, then spiraling up again to park for the night in the high-rise parking decks below their condos.

All over the gulf coast there are houses on stilts, and these are giant versions of the same idea.

The streets here are not a place to conduct commerce or meet neighbors, they are a place of transience,

a means of evacuation, a place that's ready for sacrifice to the inevitable flood.

The real city begins sixty feet above the ground, behind security gates, with views of the distant bay.