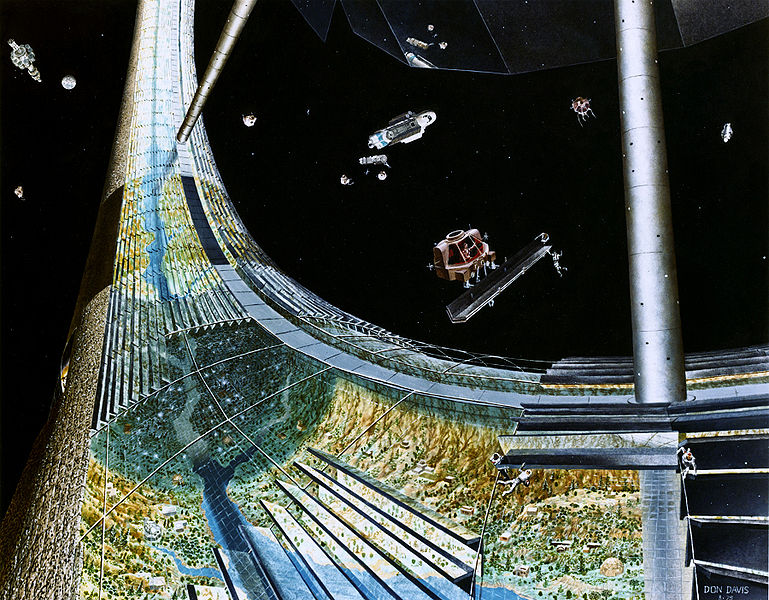

The peak of the American suburban impulse may well have been the year 1975, the year a group of earnest technocrats and back-to-the-land hippies converged to make the case for orbiting shopping plazas and ranch-style homes in deep space.

When I was a kid obsessed with astronomy, I spent hours staring at paintings by

Don Davis, an American artist best known for his sci-fi illustrations. The works that I remember most vividly were his depictions of the space colonies advocated by Princeton physicist Gerard O'Neill in the mid-1970s, which were brought to my attention recently by

a recent blog post on The Atlantic's technology blog.

These paintings were, and still are, utterly bewildering. To simulate gravity by centrifugal force, the theoretical colonies generally had a cyclindrical or toroidal design, which meant that landscapes didn't recede to a vanishing point on a horizon, but instead curved up and overhead. Meanwhile, mirrors and shades on the exterior controlled night and day cycles, and blended scenes of clouds with the starry dark of deep space. All in all, trying to figure out the logic of perspective in these paintings is like puzzling through a complicated

Escher print.

But even weirder than all that were the pastoral scenes depicted, floating around in tubes through the vacuum of space. The picture above was intended to simulate the northern Californian coast, according to

an autobiographical statement on Davis's website:

"It was painted this way under the direction of Gerard O'Neill himself, who related a recent impression of the vantage point from Sausalito being an excellent scale reference for a possible setting inside a later model cylindrical colony... I deliberately wanted to imply the challenge of trying to transplant a workable ecosystem to a giant terrarium in Space."

Many of these paintings came out of a

NASA-sponsored summer camp for space theorists held at Ames research center in 1975. In that same year, Stewart Brand, the creator of the

Whole Earth Catalog, gave O'Neill several pages to make the case for space colonies in his new publication, the

CoEvolution Quarterly.

It's easy to ridicule these space suburbs now, with the benefit of hindsight. In 1975, though, the brand-new Space Shuttle was being designed and promoted as our cargo utility truck to the heavens, and the idea of space colonies resonated with at least a few back-to-the-land hippies (like Stewart Brand) who dreamed of a new frontier in which to escape the Earthbound troubles of energy shortages, nuclear war, and the decline of American cities.

Big-name environmentalists of the era mostly ridiculed the idea of space colonies - but they still took the idea seriously enough to send in responses to the idea for Brand's magazine, something that would be hard to imagine today.

Some, like

Buckminster Fuller and

Carl Sagan, doubled down on their faith in high technology and fully endorsed the concept. But most of Stewart Brand's readers and contemporaries were more skeptical. Steve Baer, a designer of off-grid houses, had

this critique, which reads like a purloined passage from J. G. Ballard or Don Delillo:

"I don't see the landscape of Carmel by the Sea as Gerard O'Neill suggests... Instead, I see acres of air-conditioned Greyhound bus interior, glinting slightly greasy railings, old rivet heads needing paint - I don't hear the surf at Carmel and smell the ocean - I hear piped music and smell chewing gum. I anticipate a continuous vague low-key "airplane fear."

And Gary Snyder, the beat poet who practiced Zen Buddhism in the rural suburbs of the Sierra Nevada foothills, bemusedly shrugs off Brand's enthusiasm:

"Thanks for the invitation to comment on O'Neill's space colony. I'm sure you already suspect that I consider such projects frivolous, in the all-purpose light of Occam's Razor my big question about such notions is "why bother?" when there are so many things that can and should be done right here on earth. Like Confucius said, 'Don't ask me about life after death, I don't understand enough about life yet.' Anyway. I'm hopelessly backwards, I'm stuck in the Pleistocene. That is, seriously... I'm still mucking around in the paleo-ethno botany, which is a kind of zazen."

While I agree with the substance of what Snyder and Baer say, I find their commentary ironic in light of the back-to-the-land lifestyles they practiced and advocated.

Baer, after all, made his living by designing off-the-grid homes for communes like Drop City - space stations for the deserts of the southwest, in other words. And while I admire much of what Snyder wrote, I also regret that his political and environmental activism suffered from his self-imposed suburban exile in the Californian foothills. When he writes "there are so many things to be done right here on Earth," I want to shake him out of his meditation long enough to point out the racial and social iniquities in his own backyard.

In the end, isn't an idyllic sylvan landscape millions of miles away from the nearest city the logical extreme of the back-to-the-land movement that Baer, Snyder, and a million other

Whole Earth Catalog readers dreamed of? Lewis Mumford, the famous champion of closely-knit urban neighborhoods, is a more reliable critic of space suburbs, and sure enough,

his critique was the sharpest and most succinct of the bunch:

"I regard Space Colonies as another pathological manifestation of the culture that has spent all of its resources on expanding the nuclear means for exterminating the human race. Such proposals are only technological disguises for infantile fantasies."

Simply replace "Space Colonies" with "shopping centers" or "subprime mortgages", and it can still apply today in our post-space age.