Art laundry

Central Park Gates, by Jean Claude and Christo, 2005. Photo courtesy of The City Project.

Posted by

C Neal

at

10:30 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: NYC

"In 1799, New York City passed on the responsibility of constructing and maintaining a waterworks to the newly charted Manhattan Company. The company, the brainchild of the improbable team of Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, received from the state legislature a mandate to supply New York City with 'pure and wholesome' water."

"There was a banking monopoly where you had the US Federal Bank [i.e., Alexander Hamilton's First Bank of the United States] and the Bank of New York, which was founded by Hamilton, Burr's rival and victim. Burr and his company got a $2 million contract from the state legislature to bring fresh water into New York City.

They decided to spend it thusly: $100,000 on waterworks and bringing fresh water into the city — so 1/20th of the total — and $1.9 million on creating a bank!"

Posted by

C Neal

at

11:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, The Hamilton Hustle (i.e. fiscal policy), watersheds

This evening, Hurricane Sandy's storm surge will combine with astronomical high tides to give eastern seaboard cities an exciting preview of sea level rise. Forecasters are predicting storm surges up to 10 feet above the average high water mark — especially in western Long Island Sound and New York Harbor, where the storm is funneling massive volumes of seawater into the right-angled corner formed by New Jersey and Connecticut.

As I wrote last week in Grist, most big cities have buried their wetlands and creeks underground. But big storms and flood events like this one have a way of making those hidden waterways reassert themselves, as underground sewers and stormwater channels fill up beyond their design capacity and overflow into the streets above.

That can happen in unexpected places. Here in Portland it wasn't even particularly stormy today, and there was only light rain. But the astronomical high tide did push water up to the surface of Somerset Street, four blocks away from Back Cove (note the empty tree wells — similar events killed the street trees planted here in 2006 due to salt water in the roots).

Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, heavy rains may once again cause problems in the sewer-bound Mill Creek.

And in New York City's Boerum Hill and Park Slope neighborhoods, the old marshes of the Gowanus Canal may once again take over the streets. This overlay of the Brooklyn section of the 1782 British Headquarters Map shows (roughly) how far the old marshes of the Gowanus used to extend across central Brooklyn:

Posted by

C Neal

at

6:58 PM

4

comments

![]()

file under: NYC, Portland, watersheds

|

|

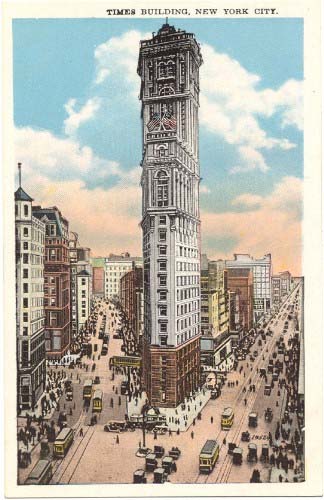

| One Times Square in 1904 (source). | One Times Square in 2010. Photo: Bernt Rostad/Flickr |

Posted by

C Neal

at

12:40 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, the built environment

Later this summer, New York City city will roll out thousands of publicly-owned bikes parked at stations, spaced a few blocks apart across three boroughs, where visitors, workers, and neighborhood residents will be able to borrow a bike for short-term rentals.

Lots of other cities have already pioneered the bikesharing idea (even Houston, Texas managed to implement bikesharing before New York did, with a much smaller 3-station downtown network that opened this spring). With origins in Paris and Montreal, bikesharing has always had a tinge of utopian socialism to it, promoting the shared use of public property over privately-owned vehicles.

But it's a socialist idea that works brilliantly, thanks to mobile technology: users can use their smartphones to locate bikes and a station near their destination, while bikeshare managers can locate lost or broken bikes with GPS, and dynamically track which stations need more bikes due to high demand. Lots of new business startups seek to duplicate the same communistic idea of letting people share their private property (whether spare bedrooms or automobiles) in exchange for small rental payments. Bikesharing makes cycling in cities easier, cheaper, and more fun, resulting in more people riding bikes for short trips in the cities where it's been established.

Private property, it turns out, is a hassle to take care of. But new technology allows people to enjoy the communitarian benefits of shared property thanks to the capitalist accountability of credit card security deposits and rental payments.

New York City's state-owned bicycles wholeheartedly embrace this ironic marriage of utopian environmentalist socialism with hard-nosed capitalism. They've been named "Citi Bikes," after Citibank, which contributed a $41 million for the naming rights.

Wall Street quants riding to work like Maoist factory workers (although even Maoists own their own bikes) will do so astride bikes plastered with the Citibank logo, and pay at stations that prefer MasterCard, another corporate sponsor.

And so here is a photo, via Streetsblog, of three transportation policy wonks (from left: NYC Deputy Mayor Robert Steel, Alta Bikeshare CEO Alison Cohen, NYC DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan) and three billionaires (Mayor Michael Bloomberg, MasterCard CEO Ajay Banga, and Citigroup CEO Vikram Pandit).In a few more years, bikesharing stations will be as much a part of our stereotypical vision of the generic urban landscape as newsstands and bus shelters are today.

Posted by

C Neal

at

9:56 AM

1 comments

![]()

file under: economics, NYC, transportation

Posted by

C Neal

at

2:31 PM

0

comments

![]()

"This is the first expressway to be built across Manhattan, and we hope that the Lower Manhattan and Mid-Manhattan expressways, both of which have been the victims of inordinate and inexcusable delays caused by intemperate opposition and consequent official hesitation, will follow. These crosstown facilities are indispensable to be effectiveness of the entire metropolitan arterial objective of removing traffic through congested city streets."

Looking west towards New Jersey over the new Trans-Manhattan Expressway and the George Washington Bridge bus terminal. Photo courtesy of the Port Authority of NY-NJ.

Looking west towards New Jersey over the new Trans-Manhattan Expressway and the George Washington Bridge bus terminal. Photo courtesy of the Port Authority of NY-NJ. George Washington Bridge bus terminal. Photo by gezellig-girl.com.

George Washington Bridge bus terminal. Photo by gezellig-girl.com. Two of the four Bridge Apartment towers, which mark the path of the Trans-Manhattan Expressway beneath. Photo by Zach K.

Two of the four Bridge Apartment towers, which mark the path of the Trans-Manhattan Expressway beneath. Photo by Zach K.

Posted by

C Neal

at

6:17 PM

2

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, Pavement pollution

Posted by

C Neal

at

8:03 AM

1 comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, the built environment

Posted by

C Neal

at

9:29 PM

2

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, watersheds

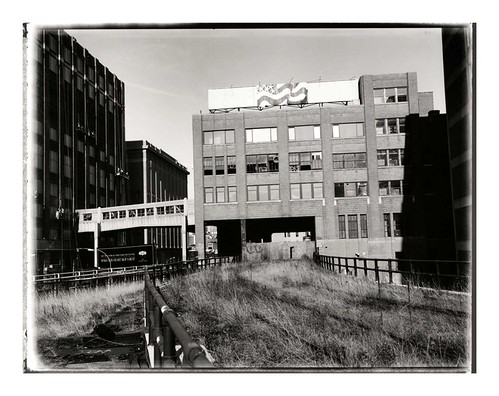

Left: the High Line in 2007 and in 2010: cultivating native plants and overpriced condo towers. Click to enlarge.

Left: the High Line in 2007 and in 2010: cultivating native plants and overpriced condo towers. Click to enlarge. And in 2009, via Inhabitat:

And in 2009, via Inhabitat:

Over the years, more dust, leaves, and soot blew in. Each fall, the topsoil gained another layer of dead grass and leaves from pioneer weeds like goldenrod, Queen Anne's lace, and Ailanthus Altissima... the new High Line park will have benches, new concrete paths, easy access from the street level, and drought-tolerant landscaping that mimics the wild weeds that inspired the park.When the new park opened in 2009, we were in the middle of a huge financial crisis that seemed to hold out the promise of being that "next large disturbance." Here's an excerpt of the post I wrote at the park's grand opening:

It might seem like an interruption and commodification of the wild successional process, but New York is nothing if not habitat for homo sapiens, and the new High Line fits in perfectly with New York's typical neighborhood succession: places once run-down and diverse inexorably become unaffordable and boring. At least until the next large disturbance, anyhow.

In the new economy, the High Line feels a lot weirder. It was meant to be a futuristic preserve for New York's past - especially its overgrown lots and abandoned industrial infrastructure. Now that the park is open, though, the ultra-slick High Line feels a bit out of place. Instead of evoking New York City's past, the High Line looks more like an expensive simulation of conditions in inner-city Detroit, or of a foreclosed backyard, or of any of the thousands of newly-defunct car dealerships nationwide. Those conditions were rare in New York City two years ago, but now that they're fairly commonplace in society's consciousness, the High Line seems more artificial and contrived.Now that I've been there, though, I realize that the High Line doesn't feel anything like Detroit or an abandoned car dealership. That's its problem: it lacks any relationship to the economic or environmental conditions of the city. Instead, it sits aloof from the street, a walled garden guarded against the weeds and the history that used to reside there.

Posted by

C Neal

at

4:40 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, psychogeography, the built environment

“The 7 line is a physical, urban transect through New York City's most diverse range of ecosystems. Affectionately called the International Express, the 7 line runs from Manhattan's dense core, under the East River, and through a dispersed mixture of residences and parklands before terminating in downtown Flushing. Safari 7 circulates an ongoing series of podcasts and maps that explore the complexity, biodiversity, conflicts, and potentials of New York City's ecosystems. Tours are available online and can be experienced independently, or in group expeditions and workshops organized by the Safari 7 team.”

Posted by

C Neal

at

7:44 PM

1 comments

![]()

file under: inner-city wilderness tours, NYC, the built environment, transportation, wildlife

Posted by

C Neal

at

10:17 PM

1 comments

![]()

Posted by

C Neal

at

3:08 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, inner-city wilderness tours, NYC, psychogeography

Posted by

C Neal

at

10:38 AM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, inner-city wilderness tours, NYC, the built environment

Posted by

C Neal

at

9:13 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, watersheds

Back in the late 1970s, John Carpenter wrote and directed a movie based on the premise that Manhattan Island would be abandoned and turned into a maximum-security prison by 1997.

"Escape from New York" (which has a highly recommended Wikipedia article) nicely sums up the pessimistic attitudes people had about our cities only 30 years ago. The movie was actually filmed in East St. Louis, where a massive urban fire had reduced hundreds of downtown blocks to rubble. The city had suffered one of the nation's worst cases of white flight, and its bankrupt government had no objections to its streets being used as a post-apocalyptic movie set.

Posted by

C Neal

at

7:38 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: history, NYC, psychogeography

This is a red-tailed hawk that lives in Washington Square Park, in the middle of New York City's Greenwich Village. It is eating a pigeon on top of the New York Daily Photo blogger's air conditioning unit.

This is a red-tailed hawk that lives in Washington Square Park, in the middle of New York City's Greenwich Village. It is eating a pigeon on top of the New York Daily Photo blogger's air conditioning unit.

Posted by

C Neal

at

3:25 PM

10

comments

![]()

file under: NYC, the tropospheric wilderness, wildlife

Posted by

C Neal

at

7:13 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: NYC

In hindsight, New York didn't fall. In fact, the city is worth trillions of dollars and is basically ruling the planet. And so, flush with cash and ambition, the city is looking to the future with an optimism it hasn't had in decades.

In hindsight, New York didn't fall. In fact, the city is worth trillions of dollars and is basically ruling the planet. And so, flush with cash and ambition, the city is looking to the future with an optimism it hasn't had in decades. In spite of the references to "opening" and "maintaining" the city, every one of the ten goals involves making New York, and by extension, America, more sustainable. The plan claims that "New York is one of the most environmentally-efficient cities in the world." The world can disagree, but certainly NYC is the most efficient place to live in the United States. Imagine how much worse off we would be if New York's 8.5 million people - almost 3% of the nation's population - lived the same SUV-driving, McMansion-living lifestyle that the rest of America practices, instead of riding subways and living on an average of two-hundredths of an acre? If a million more people can live there instead of Peoria, the world will be in comparatively better shape.

In spite of the references to "opening" and "maintaining" the city, every one of the ten goals involves making New York, and by extension, America, more sustainable. The plan claims that "New York is one of the most environmentally-efficient cities in the world." The world can disagree, but certainly NYC is the most efficient place to live in the United States. Imagine how much worse off we would be if New York's 8.5 million people - almost 3% of the nation's population - lived the same SUV-driving, McMansion-living lifestyle that the rest of America practices, instead of riding subways and living on an average of two-hundredths of an acre? If a million more people can live there instead of Peoria, the world will be in comparatively better shape. Even though the plan doesn't mince words about the problems that might face the city (flooding, blackouts, all-day rush hours), the overall tone is strikingly optimistic. These goals might be prerequisites for New York's continued dominance, but they also give good reason for the world to keep following New York's lead.

Even though the plan doesn't mince words about the problems that might face the city (flooding, blackouts, all-day rush hours), the overall tone is strikingly optimistic. These goals might be prerequisites for New York's continued dominance, but they also give good reason for the world to keep following New York's lead.

Posted by

C Neal

at

2:26 PM

0

comments

![]()

file under: citizenship, energy, global warming, NYC, watersheds

Posted by

C Neal

at

8:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

excerpted from a quote of Don Pedro, a Spanish stereotype and frame-narrative foil in Melville's Moby Dick:

"Hereabouts in this dull, warm, most lazy, and hereditary land, we know but little of your

vigorous North."

See also the inaugural post.