A few years ago, a millionaire from New York came into South Portland, Maine and proposed to build 41-story twin towers on top of a convention center/plastic surgery hospital. The complex also would have included an aerial tram over the harbor to downtown Portland, and an extended-stay luxury hotel in one of the towers where plastic surgery patients would recover. Like many of his colleagues, this developer was wealthy in cash and ego and bankrupt in taste.

Now another strange and unlikely plan is taking shape further north, in the quaint seaside town of Wiscasset. A cadre of Connecticut real-estate developers are proposing a new coal gasification power plant just north of the shuttered Maine Yankee nuclear reactors.

Coal gasification is a process that's been around for decades now: it bakes coal at high temperatures to break the stuff down into energy and component chemicals, some of which can be synthesized into diesel fuel or natural gas (

wikipedia has the chemistry lesson). Compared to a conventional coal plant, there are, indeed, some significant advantages: sulfur and mercury in the coal gets baked out and separated instead of going up the smokestack. The gasification process is also more efficient, using less coal to produce more energy. And a byproduct is syngas, which can be converted either into natural gas or diesel fuel (the gasification process was used extensively in Germany during WWII due to oil and gas shortages).

The Connecticut real estate developers are proposing to manufacture synthetic diesel fuel, which will also have some marginal pollution benefits over typical diesel, from the new plant in Wiscasset.

Sounds good, right? The developers also claim that the plant will "support... the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI)... to reduce overall carbon emissions" and that it "bolsters Maine's self-reliance by reducing transportation fuel imports." These and other "top ten local and regional benefits" can be found on the

Twin River Energy Center web site.

But the gee-whiz attitude is either misleading or misguided - probably some combination of both. There are some glaring instances of bad math and bad science in the developers' "fact" sheets. Here's a gem: "Diesel engines are 26% more fuel efficient than gasoline engines and therefore emit 26% less CO2." In fact, the cetane molecules in synthetic diesel contain a lot more carbon per gallon than gasoline's isooctane, and diesel emissions include heat-absorbing soot particles that are extremely powerful greenhouse pollutants.

If they were better at math, the developers would avoid the carbon question like the plague, because there's no denying that this proposed plant would convert millions of tons of coal (carbon) into global-warming CO2. This plant would only "support" RGGI insofar as it would have to buy up literal tons of carbon-pollution credits on the regional market.

Now, theoretically, the plant might at some point be able to "sequester" the greenhouse gases it produces them and, I don't know, shoot a rocket full of its CO2 to the moon, or something. The technology doesn't exist yet, but our friends in the coal lobby assure us that they're working on it.

As for other pollutants, gasification removes

most mercury and sulfur from the smokestack emissions, but there's still enough left coming out of the tailpipe to make this proposed plant one of the biggest, if not

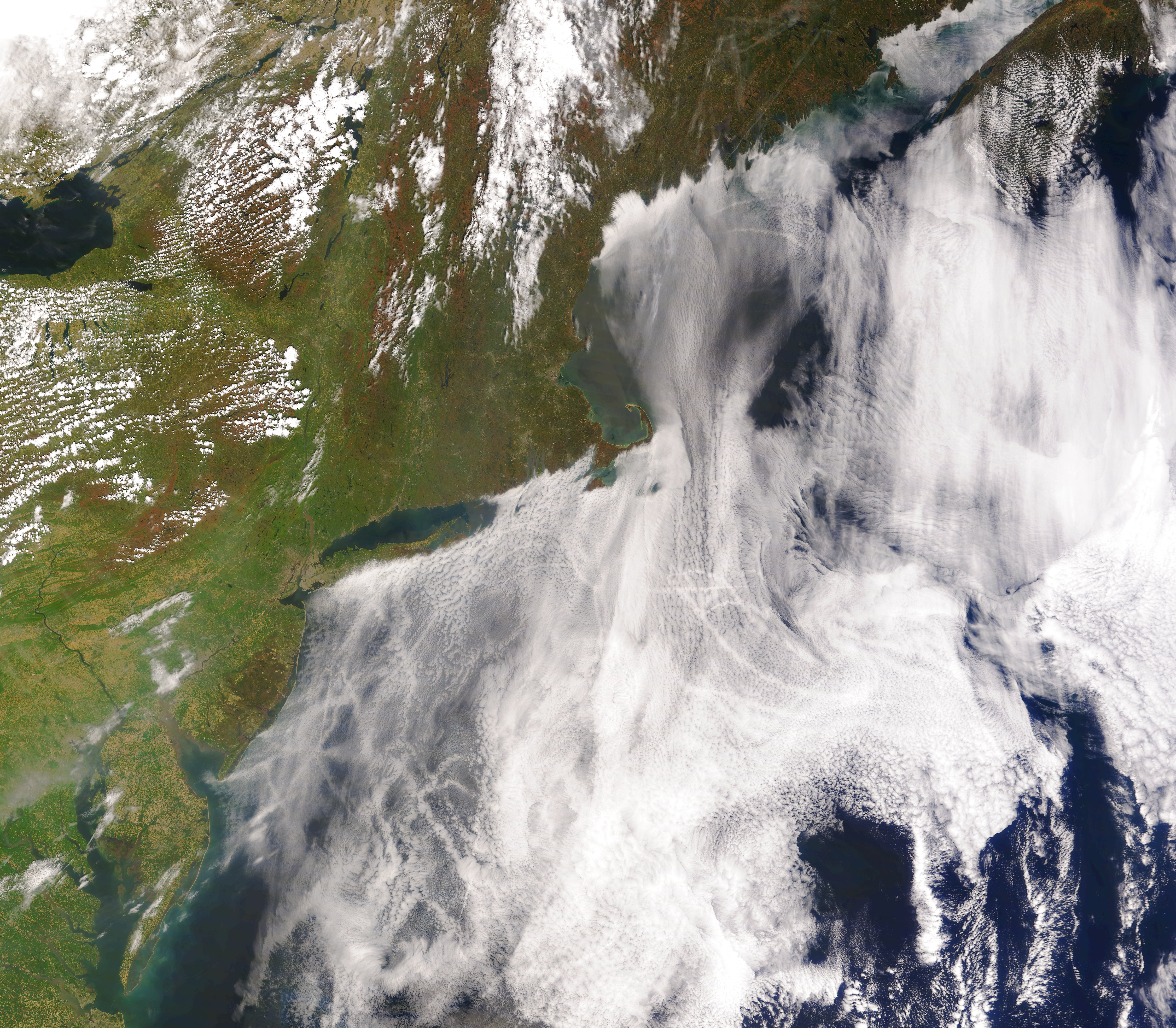

the biggest single source of mercury and acid rain pollution in Maine. At least the prevailing winds will blow it down into the wealthy lungs in the midcoast region, and not into mine.

Finally, Maine is not a coal mining state, which undermines the idea of rugged "self-reliance". Coal would have to be imported, and most of it would probably come from mountaintop removal strip mines in impoverished regions of southern Appalachia (see photo above).

There are shadowy economic problems as well. Most of these gasification plants still require huge government subsidies, even with demand for their natural-gas and diesel byproducts at an all-time high. The industry argues that a few early subsidies will reduce technology costs to the point where all new coal plants can adopt the gasification process in the future. But this argument presumes that we'd want to build new coal plants, which seems like a foolhardy assumption in the face of imminent climate disaster. At the very least, carbon taxes and regulations like RGGI will make any kind of coal power more and more expensive... so why not save our subsidies for unambiguously clean technologies?

In short, all of the "advantages" of "clean" coal only look good when you compare the idea against the extremely bad example of a conventional coal plant. Otherwise, "clean coal" looks like... well, it's definitely not shinola.

An opposition group has already emerged in Wiscasset, but judging by the developers' amateurish pitch and the inherent lousiness of the idea, they shouldn't have to work very hard.