Economic delerium and architectural fever-dreams

"In the center of Fedora, that gray stone metropolis, stands a metal building with a crystal globe in every room. Looking into each globe, you see a blue city, the model of a different Fedora. These are the forms the city could have if, for some reason or another, it had not become what we see today. In every age someone, looking at Fedora as it was, imagined a way of making it the ideal city.."

For some reason (perhaps for solidarity among dying industries - they still print an Automotive section as well), the New York Times is still publishing an entire "Real Estate" section on the weekends. But Sunday's edition included an article that was highly worth reading: a feature on the unbuilt architecture of the Roaring Twenties.

The speculative binge of the late twenties seemed, for a time, like a great boon to architects and tall buildings. "In Manhattan in 1928, plans were filed for 14 buildings of 30 stories or higher, but by the next year the number was 52," writes author Christopher Gray.

Then reality set in when the stock market crashed at the end of 1929: "of these 52, just 19 would be built [in the midst of the Great Depression]. This ambitious cohort included designs that were indeed completed, like the Waldorf-Astoria and the Empire State Building."

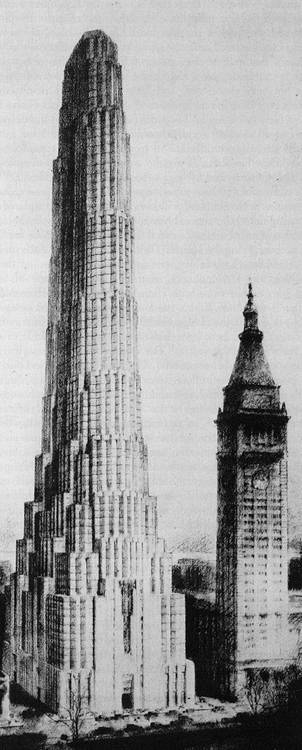

At left, a 1929 proposal for a 100-story office building for Metropolitan Life next to Madison Square Park. Had it been built, it would today be the tallest building anywhere on the East Coast.

Most of our city skylines owe their existence to artificial economic booms of the past century. But the unbuilt visions can be even more impressive: like the fever-dreams of a delerious patient, we look back and wonder what they were thinking.

There are more examples from Houston, Texas in the early 1980s, when a boom in oil prices was generating spectacular real estate speculations for the city where most oil companies are still based.

The Bank of the Southwest proposed the 82-story skyscaper at right in 1982. When OPEC let loose its oil supplies in the mid-1980s, the oil price collapsed, along with Houston's economy and this proposal. A few months later the Savings and Loan crisis put the nail in the coffin for builders.

Of course, a lot of what happened in 1929 New York and 1980s Houston is happening again today, everywhere. In the delerium of an economic boom, architects and developers rushed to outdo each other with tall buildings and famous architects. Some of those architectural hallucinations are still being built, just as the Empire State Building was finished in 1931 (New York's current-tallest skyscraper didn't turn a profit until 1950).

Others buildings will enter the world of reality as deformed, misshapen siblings to their boom-era blueprints. Witness the Las Vegas condo hotel that, in February, responded to the foreclosure crisis by amputating the top 21 stories from the building mid-construction. The developer of that project, appropriately enough, is MGM Mirage.

But most of these dream-buildings will be unbuilt and forgotten. "The Missing Skyline," a recent post on Curbed, is a good survey of the New York City that New York City might have become if the infection of financial insanity had been allowed to continue a bit longer...

3 comments:

I took the link to the Las Vegas hotel article. It's certainly a great emblem for the times, but I feel like you've done a bit of false reporting here - the article portrays human error due to bad construction as the reason for the amputation. I agree that in 2004 they almost certainly would have figured out a way to make it happen, but it still doesn't seem quite as simple as "Vegas' response to the foreclosure crisis".

Do you have other sources that flush out the economic reasons a little better? Because I'd love to believe it's true...

Karen -

Thanks for keeping me honest. True, the developers claim that a construction error is to blame for the shortening. But in normal economic times, that kind of construction error would have been corrected. As the architect interviewed in the article notes, this is unprecedented.

I also don't feel like the source is altogether trustworthy in this case - blaming "faulty rebar" instead of the foreclosure crisis seems to better suit the interests of the developers, who are still trying to sell three other high-rise condo buildings in a city that's been whammied especially hard by the credit crisis and too many empty homes. Blaming the crisis might scare away potential customers wary of buying into a high-rise ghost town. Blaming "faulty rebar," while still embarrassing, at least gives the developers a chance to maintain an illusion of confidence in their project.

In short: "faulty rebar" is not an insurmountable construction problem. But combined with a huge foreclosure crisis that's hitting Vegas especially hard, it's a problem that's not worth solving.

BTW, the same thing may be happening (on an even larger scale) to a Frank Gehry-designed high-rise being built in lower Manhattan:

http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20090319/FREE/903199969

Post a Comment